On a crisp fall evening of November last year, a young woman was heading home after a night out with friends. In the early hours of the morning, she reportedly sped down the street and hit a parked car. Confused and discombobulated, she wandered to a nearby house in search of help, and after banging on the door, she watched as it opened to a man behind the screen. He was standing there with his shotgun raised towards her. Before she could say anything, he shot her in the face.

The facts of this story make it particularly shocking and horrific, but it is made more complicated by the fact that Renisha McBride was African American and her killer, Theodore Wafer is white.

Some scholars have argued that racial bias has declined due to strengthening of egalitarian social norms, but anyone who tries to argue that racism is a thing of the past is not seeing the full picture. It is a complex and deeply ingrained problem in our society today that has been made all the more clear for me since moving to Chicago. I hear it in the personal story of a friend who was faced with the question “do you belong here?” in the elevator of his own building; I see it in reports of the persistent tragedy of gun violence in South Side Chicago; I read it in the news cycles about Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown; story after story demonstrating hatred and prejudice, on all sides.

We live in a world in which displaying outward prejudice towards others is no longer socially acceptable. We know it’s not ok, and most people try to behave in ways that do not imply obvious prejudicial feelings. We think we know ourselves and how we will react in a given situation, but what if our brains hold beliefs that we are not consciously aware of? And if this is the case, how could we even detect these hidden beliefs?

We can turn to neuroscience for answers.

Modern neuroscience has the ability to probe the nervous system in ways that go beyond our reported and conscious experience. It can detect processes that are going on underneath the surface, and doing so might help us better understand why people who sincerely believe they are not racist might still make racist decisions in the heat of the moment.

Let’s start at the beginning: looking at a face.

Our eyes pick up information about how that face reflects light. You might think that once this information reaches the eye, it gets sent into the brain to be processed and interpreted. While this is partially true, the story is a little more complicated.

Face Area in the brain

There is an area in the brain that is specialized for interpreting faces. When the wolf sees the attractive lady face, his own face area activates (the orange blob in the back of the brain, above the ear).

Research has shown that this area activates more in response to members of one’s own racial group (your ingroup) when compared to other racial groups (your outgroup). As early as 170 milliseconds after seeing a face, this difference shows up in electrical activity coming from this face area. The solid line (in the figure below) reaches a lower point, representing an increased response to people within an individual’s group.

This evidence suggests that at the very earliest stages in processing a face (.17 seconds after!), information about social group membership may be influencing our response at an unconscious level; therefore, visual perception is not just a direct sequential export of information from the eyes to the brain, but instead a complicated mixture of the perceived subject and a whole lifetime of previous experience and cultural exposure. It would be like having an unusual camera; instead of taking an objective picture representing items in the world, it would produce a doctored image that put some parts of the image in focus and make others blurry based on previous pictures taken.

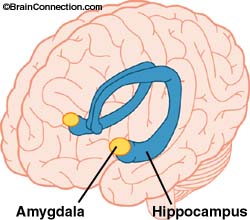

The Amygdala

We also see racial differences emerge in a small structure in the brain called the amygdala, an almond shaped cluster of cells that are thought to be involved in memory, decision-making and emotional reactions.

Jaclyn Ronquillo and her colleagues carried out a study where they flashed photos of faces to participants and measured brain activity. The faces were either light or dark versions of white or black individuals (see examples below). They found that darker skin tones elicited a greater amygdala response (“white dark”, “black light”, and “black dark” bar graphs labeled below), which they explained as a heightened fear response. Unexpectedly, this trend also shows up in African-American subjects viewing darker skin tones, suggesting that the amygdala may be responding to cultural exposure rather than just ingroup/outgroup categories.

These two brain regions, the face area and the amygdala, seem to be responding to slightly different things. The face area activity is related to familiarity with the face (have you seen this face before?); the amygdala response seems to be more of a learned fear response based on previous experience with the world. These research studies reveal some potential sources of the bias that is able to hide in the depths of the brain.

If these biases exist, how are we able to appear unbiased?

Humans must constantly navigate a social world, and they need to play by the rules of the culture to be accepted. People must try to curb any unwanted influences of implicit stereotypes, an action that seems to involve a brain region that detects internal conflict: the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Activity in this part of the brain has been associated with a person’s motivation to respond without prejudice. During times of internal conflict, the ACC will activate, helping to hide our bias not just from the outside world, but also from ourselves!

So we are left with a battle in the brain.

A brain faced with overt questioning regarding race may have the cognitive control to produce the socially acceptable answer (through ACC involvement); however, processes that bypass conscious awareness and produce implicit bias may still be able to influence behavior when decisions are not carefully evaluated.

How does this help us understand what happened to Renisha McBride?

Is it possible that Theodore Wafer, stumbling to his door in the middle of the night, committed this terrible atrocity because of the signals coming from his face area or amygdala? Could this have been prevented if his ACC had kicked in to regulate his behavior?

People are convinced that they excel at seeing things objectively and without bias, but stories like this one and neuroscientific data tell us otherwise. The brain is constantly filling in the blanks with past experience, making shortcuts that help us sift through infinite amounts of information every day. Gaining a deeper understanding of the biological basis of racism can better arm us against allowing it to influence the decisions we make every day.

What can we do when these shortcuts do more harm than good?

The first step comes from being aware that implicit bias exists, and it is able to influence behavior in ways we may not be aware of. Knowing that our nervous system may be working behind the scenes in ways we don’t directly experience is the first line of defense.

Research also suggests that we can change these supposed automatic responses by developing a different framework and redefining the boundaries of the ingroup. The automatic bias response is eliminated when the definition of a group is shifted. This could be a shift from focusing on racial boundaries to focusing on members of one’s own sports team. When an individual sees a face as a fellow teammate rather than a member of a different racial group, she no longer displays a different response to racial groups that are not her own.

In this country, prejudice against African Americans is one clear example of ingroup/outgroup mentality, but this concept can be applied to any of the many conflicts seen around the world. Whether it is a line drawn regarding race, religion, or gender, all the overarching concepts stay the same.

This is a complicated issue that is deeply ingrained in history, culture and politics, but I truly believe that understanding the role the brain plays in social prejudice and stereotyping is a crucial step towards decreasing and ultimately eliminating them.

Sure, but how is this relevant to me?

Not many people will be faced with a stranger on their porch in the middle of the night or required to make a snap judgement while holding a gun; however, these principles are highly relevant in any kind of workplace environment as well. Check out this great video that google produced about implicit bias.

We need to take responsibility for understanding what assumptions we make on a day to day basis, and shift the way we view others. Ask yourself, who is in my group and could these lines be changed? Can a group simply be fellow city-dwellers, leaving race out of it? What would the world look like if everyone became more aware of the biases they have?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this!

Citations:

Lieberman, M.D., et al., An fMRI investigation of race-related amygdala activity in African-American and Caucasian-American individuals. Nat Neurosci, 2005. 8(6): p. 720-2.

Ratner KG, Amodio DM (2013) Seeing “us vs. them”: Minimal group effects on the neural encoding of faces. J Exp Soc Psychol 49: 298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.017

Ronquillo, J., Denson, T.F., Lickel, B., Lu, Z., Nandy, A., & Maddox, K.B. (2007). The effects of skin tone on race-related amygdala activity: An fMRI investigation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2, 39-44.

Reblogged this on NPHR Blog and commented:

Editor’s Note: Although our blog is public health-focused, we also think it is important to understand medical research and basic science to see how these worlds inform the public health world and vice versa. A fellow NU doctoral student has written a thoughtful essay on her blog Gray Matters about the neuroscience behind racial and other biases, which we are re-posting here. As public health workers and scholars, dealing with biases is an unavoidable part of our lives and work. From gun violence to health care disparity, prejudice and stereotyping alters our behavior – consciously or unconsciously. Perhaps understanding the biology behind our biases might help remove these unconscious prejudices. We encourage you to read this take on stereotypes, and to check out the Gray Matters blog!

LikeLike

I love what you’re doing with this blog – bringing science to the people. Thank you for breaking down complex topics in a way that is approachable to the average person. Keep the posts coming!

LikeLike